Bureaucratic Bloat

Some thoughts on bureaucracy.

PHILOSOPHYPOLITICS

Bureaucracy is one of the things in life I hate more than almost anything else. I was looking at the org chart of the company I work at the other day. We have a CEO who has 11 other executives in the C-Suite. Those 11 then go on to have 94 VP-level direct reports who have a further 489 Director-level direct reports. Then the middle management starts. Taken all together, we have 595 individuals making up the top partition of the pyramid.

It's guaranteed that every single one of these individuals is at least making 100k per year. So running with that math, this top portion of the pyramid is compensated to the tune of at least 59.5 million dollars. Realistically, it's probably much higher. A reasonable range would probably put the 59.5 figure as the low value and maybe 200 million as the high end. Now, having these people paid this much in and of itself isn't a problem, provided they're generating sufficient value to justify their pay.

That's the interesting thing about management. When you have an individual employee, you can roughly approximate how much they're worth. They're making direct contributions that can be valued. However, as you move into management, managers are no longer making direct contributions. Instead, they're primarily being paid to make decisions and manage their direct reports. This makes valuing them rather difficult which has some interesting consequences.

A good manager will increase the productivity of his employees. Or at least that's what they'd like you to think. In many cases, I think a good manager reduces the productivity of an employee by a minimal amount. I guess you could say there's the synergy view of management and the subtractive view of management.

In the synergy view, let's say you have a team of five individuals who each produce one unit of productivity. In theory, a good manager would be able to take those five individuals and generate surplus productivity. So instead of each member of the team producing one unit, they might produce one and a half. For the manager to justify his existence, he and his direct reports must produce enough productivity to cover the cost of the team as well as the cost of the manager. In the example from above, a minimum of six units of productivity need to be generated. Ideally, more than six would be created which would result in the manager creating synergy and providing good value to his or her company.

However, a lot of people have stories about having managers who absolutely suck. If anything, having crappy managers almost seems to be the norm. Enter the subtractive view of management. In this case, our five team members produce a maximum of five productivity units. If they have a good manager, they'll produce five units. However, if they have a sucky manager, then their individual production will be diminished by having to deal with their manager.

As a general rule, it is ideal to have decision-makers be as close to the focus of the decision as possible. This is on account of the fact that those closer to the focus of a decision tend to have a better understanding of the details and specific information relating to the decision. This is one of the things that makes capitalism work. Individuals with specific information are the ones making decisions instead of individuals a few layers removed. The owner of the store is the one who is deciding what to stock the store with.

This is what's so dangerous about bureaucracy and management. With each level of management, the decision-makers are getting further and further removed from the metaphorical trenches. Good management accounts for this by getting their hands dirty. They get their butts back in the trenches. Bad management ignores it. If the increase in the proximity of the decision was the only problem, bureaucracy wouldn't be so bad. Unfortunately, along with this trait, it also generates a very perverse set of incentives.

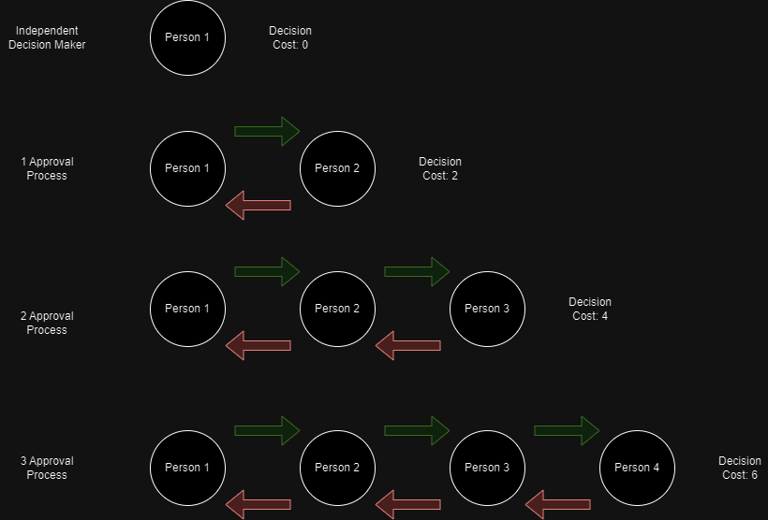

The best way to get fired in a bureaucratic institution is to make a decision you don't have the authority to make and then for the decision to go poorly. On account of this, each level of management has the incentive to be highly risk-averse and pass decision-making further and further up the tree. Every time an instance of communication needs to take place between two adjacent nodes, you incur a communication cost. As the number of approval nodes increases, the communication cost increases linearly. However, this assumes that the approval process is a single-node chain. In most organizations, the chain will be branching (needing the VP of Engineering, the VP of Marketing, etc to sign off on a decision) and the communication time will increase exponentially.

For example, communication between two people has a cost of two. Person one requests approval from person two. Person two then responds. However, if we add in person three, then we have the following situation playing out.

Each instance of having to ask for approval to do a specific action takes time. Consequently, any time more approvers are involved than the bare minimum required to make a good decision, waste occurs in the form of lost time. In cases where the situation is time-sensitive, this can be detrimental. The result of this whole deal is that an organization set up such that all members are capable of making decisions without requiring approval provided they're competent to make the decisions in question will then have a competitive advantage over their bureaucratic counterparts.

This is why it's extremely important to make sure the employees of an organization understand the mission of the organization. If the employees know what they're trying to accomplish, then they can make decisions at the individual level, cutting out the wasteful approval process.

That basically takes you to the root of the two philosophies we're discussing here. Bureaucracy is all about avoiding responsibility. The alternative is taking responsibility at the lowest level. So with respect to my own organization. As the years pass and I see it become progressively more and more bureaucratic, I can't help but shake my head. if it continues to add more and more managers who are in all likelihood subtracting value instead of adding it, company performance is going to suffer.

To wrap up, as another general rule, use the minimum amount of management required for the task at hand. Remember who on the hierarchy is actually generating the value. (Hint... It's not usually management.)