Zero Sum Games

A slight pivot from the Biblical kick I've been on as of late. This one will have a bit of overlap with the podcast. It's time to talk about games.

GENERAL

Today’s topic is zero-sum games. A zero-sum game is a contest in which victory comes at another’s expense. One example of a zero-sum game would be chess. In order for white to win, black must lose. Not counting a draw, there are no other options. Either white wins or black wins. Another example would be divvying up a pie amongst a group of hungry people. Provided there is only one pie present at the gathering, giving one person a larger slice of pie comes at the expense of another person.

Zero-sum games are interesting because they provide a basic framework for adversarial unidirectional thinking. They are simple to understand with even children being quick to grasp the concept. Unfortunately, zero-sum games are also problematic. On account of their ease of understanding, many people grasp the concept and then never move past it. The trouble with this arises when someone applies zero-sum game logic to all situations. This can often do great harm to everyone involved.

Let us examine the pie example some more. Let’s say we have Paul, Fred, and Jeff. The three of them are going to have a blueberry pie. We’ll view the situation from Paul’s perspective. How should the group split the pie? The fairest approach would be to split the pie into even thirds with every member getting an equal share. However, this approach isn’t the one that provides the most advantage to Paul. From Paul’s perspective, getting the whole pie would represent the best outcome in a zero-sum game world. Getting no pie would be the worst outcome. He can get 33% of the pie with the even split approach so it’s inherently Paul’s goal to increase his 33% split to a greater proportion. Doing this will come at the cost of Fred and Jeff. For Paul to get more than 33% of the pie, Fred and Jeff need to get less than 33% of the pie.

So, given Paul’s goal of getting as much pie as he can, how can he go about achieving this goal? One option would be trying to talk Fred and Jeff out of some of their pie. In a more complicated example, this would be a viable option, but we’ll say for simplicity’s sake that in this case, both Fred and Jeff want the pie just as much as Paul does. On account of this, if we further add the stipulation that this is the only time the trio will negotiate, in other words, this is the only time this game will be played, then we end up with a pretty serious impasse. All three members want more pie and none of them are willing to give up any pie they already have. Consequently, the only way forward is basically to resort to force. The surefire way for Paul to get 100% of the pie would be for him to kill both Fred and Jeff. The same logic applies to each of them.

Maybe now you can see the problem. This pie example is a joke, but zero-sum games are not. In real life, people who operate using zero-sum frameworks in inappropriate applications are dangerous. Sometimes you find yourself in a true zero-sum game. In those cases, all you can do is count your costs and prepare to fight to the death. However, a lot of the time, what appears to be a zero-sum game is not.

Going back to the pie example, if we assume that there will be more than one game played, then a whole new world of opportunities become available. For example, maybe it’s an option to make more pie. Instead of killing Fred and Jeff to get 100% of the existing pie, perhaps Paul could make an additional pie all for himself. That would allow him to get 33% of the original pie and 100% of the pie he made himself.

So why are we talking about this? Because I think that people who view the world as a zero-sum game are harmful to society. Dr. Orion Taraban did a YouTube video about zero-sum games with respect to dating. That’s what got me thinking about this in the first place. In one respect, he’s right. In the context of a relationship, if a man wants a particular woman, then it’s kind of like a zero-sum game. Men like exclusivity. Most men are not interested in wifeing up a woman who’s sleeping with a dozen other men. So, in the case of romance, in most cases, if a guy wants to be with a particular woman, all the other guys must be chased off. There are no other options. In other words, there is but a single pie.

In the case of romance, this seems rather depressing at first. It could have the effect of making one feel fearful of missing out on being with the one they love. Fortunately, despite what Dr. Taraban suggested, romance isn’t a zero-sum game. The truth is that some things are just universally special and completely independent of the person they’re done with. Some people indeed have a greater or lesser effect, but on the whole, many experiences are special regardless of the specific SO they’re done with.

To provide an example from my own experience. I thought the first girl I ever seriously dated was the one. I thought everything we did together was special. I relished every experience we had. When that relationship imploded, I was rather distraught because I thought that something was now forever lost to me. Fortunately, when the second girl and the third and then the fourth and so on came along, I started to realize that things weren’t like I thought. The first girl was special, but just not as special as I thought. A lot of the stuff I liked about her was just stuff available in any relationship with a girl. Because she was the only girl I had experience with at the time, I thought she was special because I only ever experienced those things through her, however as time progressed, I eventually was able to puzzle out what was special on account of her and what was special on account of relationships in general.

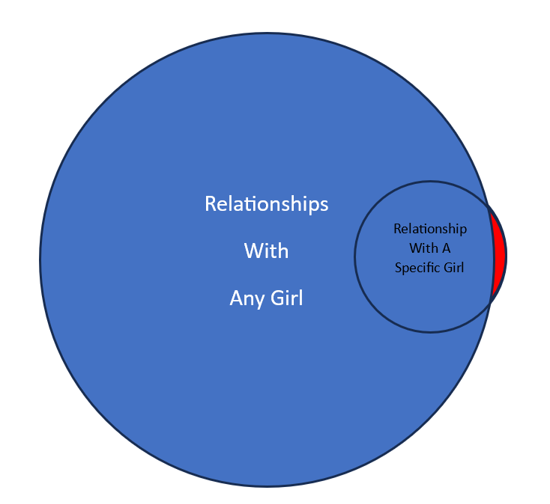

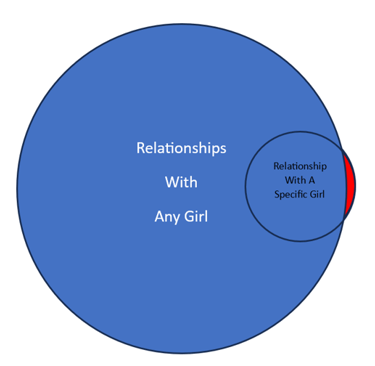

Here is a diagram that describes the situation:

The small area in red is the stuff that the first girl brought to the relationship that was unique to her. Everything else was just generic relationship stuff. To give you an example, the first girl I dated was above average intelligence. A lot of our conversations were idea-centric, which I greatly enjoyed. After the relationship ended, I was fearful that I’d never find this again because I thought it was a part of her. I thought conversations like that could only be had with her because of how great of a connection we had. However, I later discovered that complex idea-centric conversations were a hallmark of above-average intelligence and not particular to that specific girl. So, in a sense, I loved the first girl’s intelligence more than I loved her as far as conversations were concerned. Another example would be hugs. The first non-platonic hug I got was from this first girl. You can tell the difference between a platonic and non-platonic hug because the non-platonic variety has this fierce resistance to ending that’s not present in platonic hugs. Again, I thought these hugs were special to this first girl. It wasn’t until I got my first hug from the second girl that I realized that non-platonic hugs in general were special and not specifically hugs from girl number one.

So, what’s the point of this lengthy anecdote? To point out how romance isn’t actually a zero-sum game. A lot of what people want in a relationship can be gotten from anyone of the opposite sex. Hugs, cuddles, emotional support, going for long walks, intimacy, and much more. All of this stuff can come from just about anyone and still be deeply satisfying. A wise man once said to me, “Everyone looks the same in the dark.” That’s actually a paraphrased version of what he said. The true phrase can be summarized as, “It’s exceedingly difficult to distinguish the difference between one female compared to another female when using a high sensitivity probe on the inside lining of a mucous membrane in the dark.” Now replace everything sophisticated sounding with the most vulgar language you can imagine for the situation, and you have the direct quote.

Although a person may be interested in a specific person, it’s highly unlikely that person of interest is the best match. It’s statistically likely that just about anyone else in the opposite-sex population of the same age range would be an equivalent or better partner. So, in light of that, romance is often not a zero-sum game provided that you’re optimizing for your desired criteria and not for a specific person.

Moving past romance, another example of zero-sum thinking would be economics. A common economic fallacy is that getting rich requires taking money from other people. A lot of people walk around with this thought cancer every day killing their mental faculties. What they forget is that taxes are the only case of money truly being taken without just cause. In all other cases, transactions are voluntary. That means that for someone to get rich, they needed to persuade a lot of other people to voluntarily part with their money. This is usually done by providing a good or service.

People will only agree to a transaction if they feel that the transaction is beneficial to their personal interests. For example, the only way I’m going to pay $999 for an iPhone is if I feel that the phone will provide me with at least that much value. Circling back to the pie example. In economics, typically it’s possible to expand the pie. Take gold for instance. The current price of gold per ounce at the time of writing this is $2,232. At that price, any gold that can be successfully extracted from the Earth for less than $2,232 will provide a positive profit for the one doing the extracting. However, there exists gold that probably can’t be extracted for anything less than $5,000 per ounce. Beyond that, there exists space gold. So, although it seems like there might be a limited gold pie, in actual practice, as the price of gold goes up, the size of the gold pie will increase because it will become profitable to extract gold that was previously too difficult to bother with because of its difficulty to get to.

This pretty much applies across the board. One common example of a zero-sum game would be international relations. Russia and Ukraine are good examples. Right now, it seems like they’re directly opposed, creating a classic zero-sum game. For Russia to win, Ukraine needs to lose. For Ukraine to win, Russia needs to lose. Or at least that’s what the hardcore fanatics want you to believe. In actuality, the war as a whole has been a fairly large fool’s errand for both sides. The war has brought about the expenditure of a massive amount of blood and treasure for everyone involved. Had both countries focused on their own personal development, the lives lost in the war and the resources expended in it could have been used to do something useful such as improving the lives of the citizens of each respective country.

With how large Russia is, more land doesn’t really do it much good. It would be better off civilizing the land that it already has instead of trying to capture more. Aside from poor leadership, Russia has no excuse for the situation it’s currently in. The country has been endowed with every advantage a nation could ask for except for water access. However, Russia is operating in zero-sum game mode and it’s getting the results that go along with it.

With that, we can wrap up here. The takeaway of this essay is basically that you want to make sure you’re actually in a zero-sum game before you start acting like you are. Oftentimes, just a little bit of thinking outside of the box is enough to get you into a situation that is far more advantageous than directly opposing another party.